What sets Turow’s work apart from the thousands of novels it would inspire is its thorny, fleshed-out character work and interpersonal drama. He works frequently in first person or close third rather than the clinical, dispassionate, omnipotent third person, spewing plot inelegantly, if propulsively. Presumed Innocent was released the same year as Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities, and both thread the needle between the literary novel (written with an investigative journalist’s rigor) and genre fiction.

In Turow books, people make choices and say things that are odd, surprising, and fucked up. His “heroes” make the irredeemable, life-swallowing mistakes people make in real life. His borderline-serialized novels all take place in the fictional Kindle County in Illinois, a fairly transparent facsimile of Chicago’s Cook County (in interviews and speeches, the Second City native speaks with an unvarnished Midwestese accent that evokes Dennis Farina with an English degree) and his characters recur in book after book or become protagonists in their own novels. The Kindle County universe. Imagine Salinger’s Glass Family if it was full of broken, vainglorious, messy Chicago lawyers on their second or third spouse.

Within the confines of ‘90s genre, Turow was a writer’s writer, with a poetic flair, a design major’s physical vocabulary, a real facility with dialogue, and an intimate knowledge of his characters, all the way down to their favorite colors. He’s always been more interested in the human stakes of his stories than he is in taking halfhearted swings at the kind of hot-button issues that sell books and make elevator pitches land. As a genre writer, Turow is far closer to Richard Price, or Stephen King when he’s really cooking, than the other lawyer-turned-writers he was frequently lumped in with.

But as a lawyer-turned-writer, Turow is concerned with the in-session procedure of law, the cat and mouse between the bench and the defense teams laying evidentiary trails, the gamesmanship between two lawyers willing to do whatever it takes to win—including ignoring ethical and moral questions—and the palace intrigue and political maneuvering within a prosecutor’s office, even amongst lawyer/politicians all theoretically playing for the same team. He unfurls his plots through designed arguments, like a lawyer patiently building a case witness by witness from the stand, but he also understands that the idea of impartiality in law is an absurd and fanciful lie. He layers his cases with complex interpersonal connections that demand recusal, but never grants it. He’s interested in the cosmic joke, the hypocrisies and contradictions of the black-and-white institution he participated in his entire working life. These upstanding public servants, these guardians of society’s rules, are supposed to be sober and thoughtful and clinical and professional, but of course they’re also horny fuck-ups who drink too much and cross lines and need therapy.

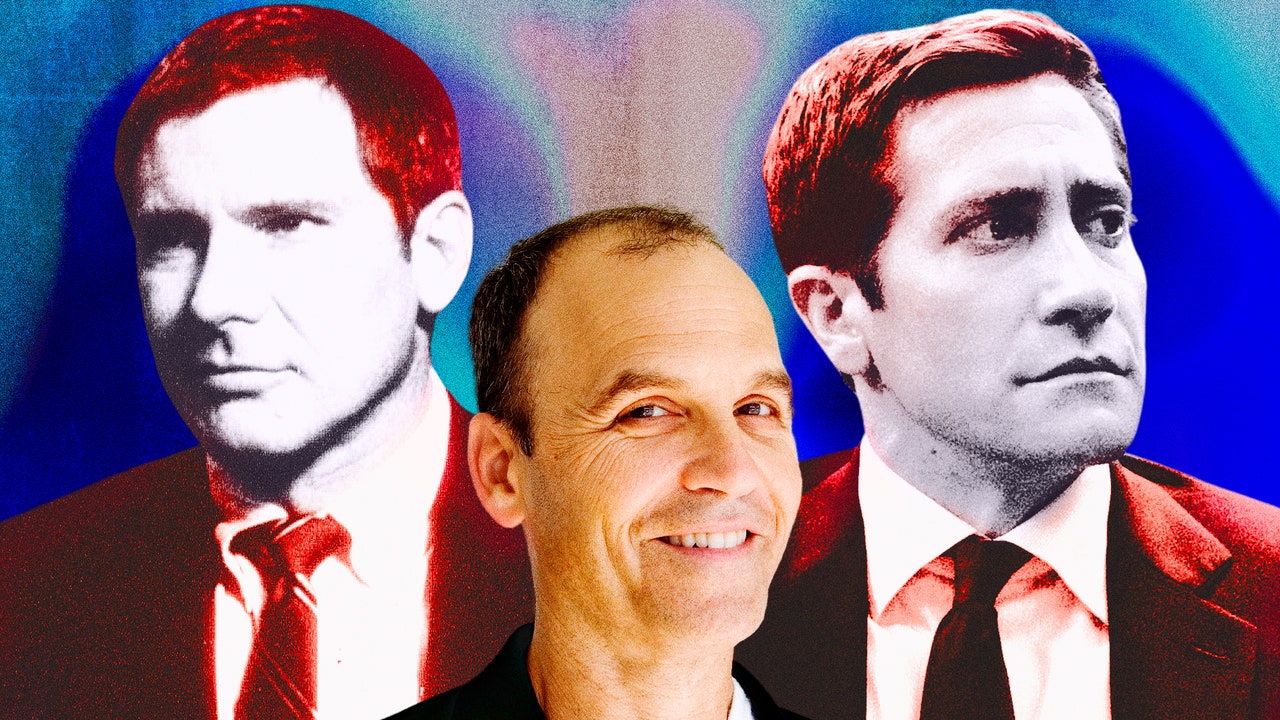

All this makes for tricky page-to-screen adaptations, and for the most part, after Pakula’s version, the television adaptations that followed in the ensuing decades have missed the magic of their source material. On the set of Presumed Innocent, Brian Dennehy told Turow that a cinematic adaptation is equivalent to the Readers Digest version of a novel, and this is largely the content we’ve ended up with. Burden of Proof, Reversible Errors, and Innocent are star-packed television “events” that mine Turow’s stories for their most maudlin, overheated beats, hitting the thriller pacing and extracting maximum suds and froth over melodramatic strings, their schlocky network packaging indicative of the era. But it’s work that elides the procedural detail and deeply-felt pathos that made Turow’s novels remarkable within the context of ‘90s airport fiction.