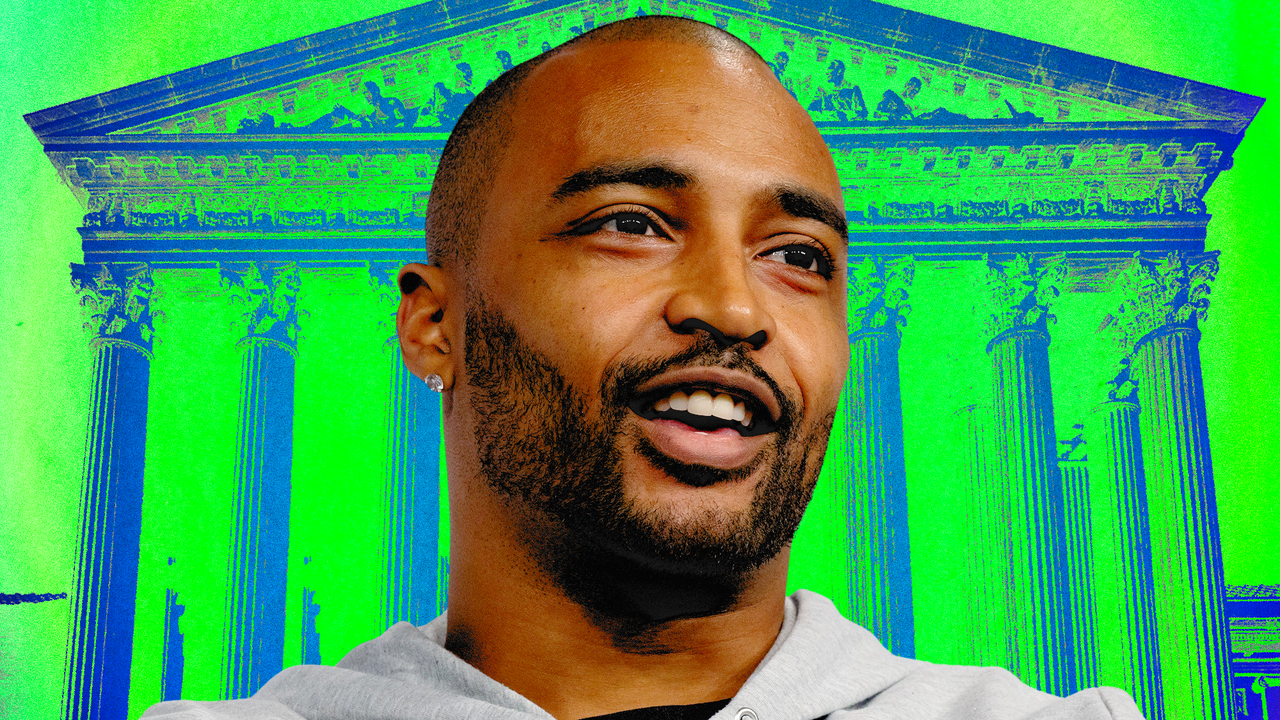

During a video call after the most recent hearings of the Clemency and Pardons Board, Baldwin spoke about his own journey from being “Angry Doug Baldwin” in the NFL to helping free people from prison. The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

You were known for your intensity on the field, and you’ve mentioned in other interviews that you struggled with the transition to your post-playing career. How did you struggle, exactly?

It was related to identity. I had been playing football since I was six years old, and I had been celebrated for my performance on that field since I was seven years old. So it became kind of a lifeline for me. And when I did not have that, I felt misplaced. I felt lost in the world. I didn’t know where I stood because nobody was giving me the affirmation of, like, “Oh, yeah, you’re doing a good job right now.”

So not having that, on top of my first daughter being born, being two and a half years into marriage…there’s so much non-instant gratification or instant affirmation when it comes to being married and having children that I think that also added to the challenge. But I also think it was a benefit to me, because I had something else to pour into. Something else that was—I don’t want to say distracting my mind from the negativity, but was pulling my mind in a different direction.

What advice had you received about how to handle retirement?

Most people that I spoke to said, “Just know it’s going to be hard.” They didn’t really have more than that. I did have one former teammate who was in the locker room before one of our games, and my mind was already like, Man, this time is coming at some point. So I just asked him, “Hey, was retirement hard for you?” And he shook his head no. That kind of shook me too, like, Dang, okay, so everybody else is telling me it’s hard. He’s saying it’s not hard.

What I learned from that was he had other things planned and ready for his retirement. He was able to pour himself into other things and find fulfillment and affirmation, whereas I was just like, “Okay, football’s up. I don’t know what’s next.” Just the nature of how I was, I couldn’t expend any energy on anything else other than football at the time, so I wasn’t as well-rounded as I would have liked to have been leaving the game.

When did you start to feel better?

I would say probably a year and a half, two years ago. It could even be less, to be completely honest—not necessarily physically, but emotionally and mentally and even spiritually, to some degree. I didn’t find this higher level of balance until probably less than a year ago.

In 2022, Washington governor Jay Inslee appointed you to the state’s Clemency and Pardons Board. The other members of the board are a court reporter, a dean of students, a former Department of Licensing director, and a public defender. How did you become involved with this?

I was doing some work on some other initiatives in the state of Washington, and one of the contacts that I was working with, he was the liaison between the governor’s office and myself. He was like, “Hey, what do you think about this? Are you interested in this?” And quite honestly, when I looked into it, I felt called to it. I felt really strongly compelled to join it.

During your playing career, you’d spoken out on issues of police reform, but also, as you mention in the hearings, your father was a law enforcement officer. Your journey when it comes to thinking about criminal justice—has it been linear, or have there been a lot of twists and turns on how you’ve thought about our justice system?

It’s a great question, and one that I don’t know if I have a good answer to, but this is how I will try to answer this: My faith has been a very strong component of how I’ve navigated the world and how I’ve felt sane in a lot of ways, and this is no different. So when it comes to—it’s hard for me even to say criminal justice or justice, because it’s an inherently flawed system, and sometimes justice doesn’t prevail, even in the system. I think I’m seeing that in some of these cases. But what I would say is that I look at the people that come before our board, and they’re just like me. They’re just human beings who are flawed … They come from really challenging backgrounds, and they may or may not have had the support in ways that would effectuate a positive change in their life, to be able to balance or counteract the challenges that they’re facing. So I look at them with a ton of grace.