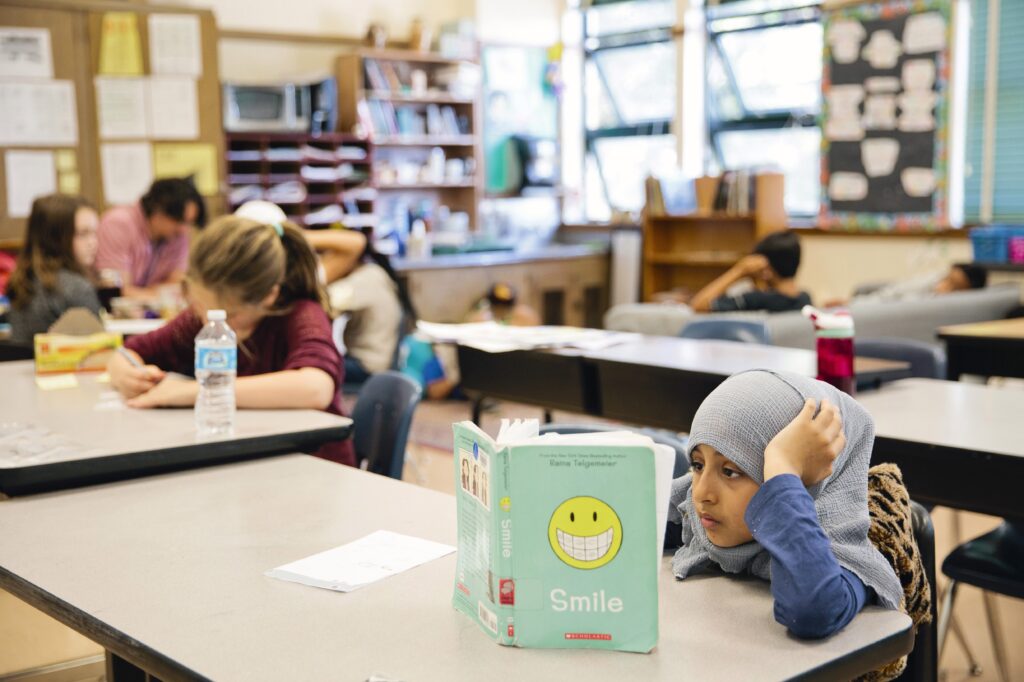

Credit: Alison Yin / EdSource

Top Takeaways

- By June 30, California schools must choose one of four screening tests recommended by a state panel.

- Most other states already have a universal reading screening test for early grades, but California has lagged behind.

- West Contra Costa went through an intensive 18-month process before selecting mCLASS DIBELS as its screening test of choice.

After a 10-year push from reading advocates, California schools are on the verge of requiring every student in kindergarten through second grade to get a quick screening test to detect challenges that could get in the way of them becoming proficient in reading.

Under 2023 legislation approved by the Legislature, every school district in the state is required to select the screening test it prefers by June 30. They can choose from among four options recommended by a state panel — and then begin administering the test during the coming school year.

California will be one of the few remaining states to introduce a universal screening test like this in K-2 grades. “This is something we have been fighting for for 10 years,” said Megan Potente, co-state director of Decoding Dyslexia CA. Her organization co-sponsored four prior bills, which did not make it through the state Legislature, until it was included in the 2023 education budget bill.

The screening test had a powerful champion: Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Newsom was diagnosed with dyslexia in elementary school and still copes with it as governor. He has become a national spokesperson on the issue, even writing a children’s book about it, titled “Bill and Emma’s Big Hit.”

Districts will only be required to administer the screening test in the K-2 grades, in part because substantial research shows that reading mastery by the third grade is crucial for a student’s later academic success.

The test is not intended to provide a definitive diagnosis of dyslexia or other reading difficulties. Instead, its goal is to be a guide for parents and teachers on whether further diagnosis is necessary and to prompt schools to provide other support services.

However, Potente, a former teacher in San Francisco Unified, pointed out that the screening test could prevent students from being placed in special education classes unnecessarily. She said her 16-year-old son, who had reading difficulties, didn’t get any intervention until after the crucial third-grade milestone.

“If we had caught his challenges earlier and addressed them with the intensive instruction that he got later, he would not have needed special education,” she said.

“Screening is just the first step. How the districts respond to the needs of students is really what’s most important,” she said.

How West Contra Costa Unified decided

West Contra Costa Unified School District’s process for choosing what test to adopt offers a window into the intensive process that at least some districts have gone through.

The 30,000-student district in the San Francisco Bay Area, serving large numbers of low-income and English learner students, first established a 20-member task force — made up of its superintendent, teachers, principals, board members, school psychologists, and community representatives — 18 months ago.

The district enlisted 150 teachers to try out mCLASS DIBELS and Multitudes, two of the four options offered by the state, and to provide detailed feedback. The district ruled out the two other options for a range of reasons.

After examining all of the information they received, district administrators recommended to the board of trustees at its May 14 meeting to select mCLASS DIBELS. (DIBELS, pronounced “dibbels,” is an acronym for Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills.)

“mCLASS DIBELS was the overwhelming choice of our teachers,” Sonja Bell, the district’s director of curriculum instruction and development, told the board.

The screening test is already in widespread use in many districts, notably in Los Angeles Unified.

One feature that appealed to West Contra Costa teachers and parents is that the DIBELS test is quick — only taking between 1 and 7 minutes. Another plus is that it can be administered by the teacher while sitting with the student. The teacher can observe the student during the screening, which provides valuable information that might not be available if the test were taken on a computer or online.

Another attractive feature was that DIBELS has a Spanish component called Lectura, which will be essential for assessing the reading skills of the district’s large English learner population.

Among the many teachers already using the DIBELS test is Barbara Wenger, a second grade teacher at Nystrom Elementary in Hercules, one of several communities served by the district. The largest is the city of Richmond.

Like many teachers in West Contra Costa and other districts around the state, Wenger has been using the test voluntarily before the task force was set up —sometimes administering it monthly to assess a student’s progress. “I can’t emphasize how important this is to our instruction,” she said.

She recounted to the board at the May 14 meeting how DIBELS helped her identify a student who could only read four words a minute, instead of the expected 50 words. She put the student in an “intervention group” and gave her structured exercises. The student, she said, is now reading 104 words a minute, making it unnecessary to place her in a special education class.

“This is something we could only have done by identifying her at the beginning,” she said.

Having selected DIBELS as the screening test, the district will turn to a District Implementation Team to oversee a multiyear rollout plan.

The district has decided to go beyond the once-a-year screening called for in the legislation and to administer it three times during the year to assess a student’s progress more regularly. A three-year professional development plan for teachers will be phased in.

Crucially, the district says it will notify parents about the results of the screening shortly after it is administered.

Multitudes, the test developed by the Dyslexia Center at UC San Francisco, received some support from teachers because it is also a one-on-one test, is free to school districts, and was created by well-regarded practitioners at UCSF. It will launch in both Spanish and English in the fall of 2025. But reviewers had concerns that Multitudes is only administered once a year and that teachers aren’t familiar with it.

Like many districts, West Contra Costa is already using i-Ready, a screening test for early readers. But the test was not on the list of the four approved by the state. In addition, there were concerns that i-Ready is an online assessment, and just accessing it electronically presents some challenges to students, especially incoming kindergartners.

Nystrom Elementary’s Wenger said that DIBELS takes significantly less time to administer than i-Ready. It also shows how far a student is from their grade level, she said, but doesn’t flag kids in kindergarten who would benefit from intervention early on.

DIBELS also has a clearer way of communicating results to parents, Wenger said. I-Ready, by contrast, “has a very complicated, confusing, and ultimately overwhelming, report home.”

Although supportive of the test, West Contra Costa board member Demetrio Gonzalez-Hoy expressed concern that the test would add to the testing burden students are already experiencing. “We have so many tests already,” he said.

Bell, the director of curriculum instruction and development, reassured him that the DIBELS test is brief, and that teachers will be careful not to overtax students or push them beyond their ability. “They’ll stop when they see students have had enough,” she said.

As part of its implementation, the district collaborated closely with GO Public Schools, an advocacy organization, to get broad community input, especially through the organization’s Community-Led Committee on Literacy.

Natalie Walchuk, vice president of GO Public Schools and a former principal, said the process of choosing a screening test has become “a catalyst for meaningful instructional improvement” in the district. She praised the district for “going far beyond the minimal requirements” in the legislation.

Potente pointed out that the screening test could prevent students from being placed in special education classes unnecessarily. She said her 16-year-old son, who had reading difficulties, didn’t get any intervention until after the crucial third-grade milestone.

“If we had caught his challenges earlier and addressed them with the intensive instruction that he got later, he would not have needed special education.”